Fire

What does it take to be a fire for your family?

An audio version of this essay is available on The Dad Bod podcast.

Work. We love, hate, want, and need it. For the lucky few, work not only pays the bills but feels like an expression of one’s true self. More typically, work ranges between frenemy and arch nemesis. Either way, what a person does for a living is a window into their life and who they are. This is where my conversation began with Edwin, whom I met through his brother-in-law Charlie, whom I met through Carlton, my friend and mailman whose aphorisms have profoundly influenced my life.

“I work for the Department of Education of New York City. I am what they call a fireman,” Edwin tells me, a job title reflecting the job’s namesake responsibility of shoveling coal into the boiler to keep the school warm. Although that specific task no longer exists, the job’s title and ultimate responsibility remain: take care of the kids by taking care of the building.

Edwin calls it a “dirty job,” an ironic description because the end goal of this dirty job - all dirty jobs, really - is to take what is dirty and unprepared and make it clean and ready.

I would also describe it as an “invisible job.” It’s invisible by necessity, performed behind the scenes and at odd hours when no one is around. It’s also the kind of job that no one notices when it’s done well, but everyone notices when it’s done poorly.

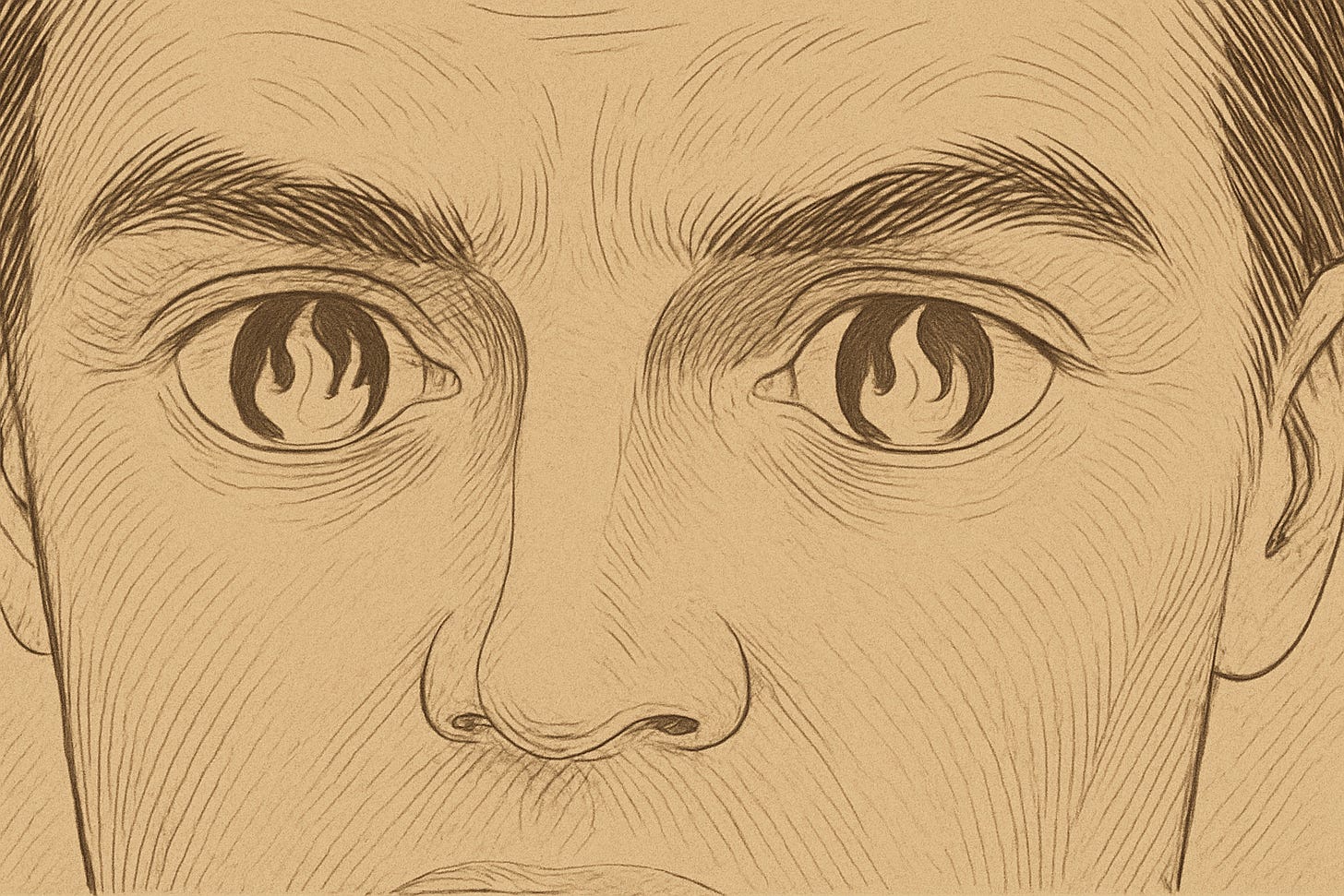

So I’m imagining now a twenty-something Edwin arriving at work at 3 AM on a cold, dark winter morning to tend the invisible fire that warms the school. With a shovel in his hands and flames flickering in his eyes, Edwin’s thinking about the weekend: a much-needed haircut on Saturday so that he’s presentable on Sunday for a first date with Pat, whom he’s been getting to know through late night phone conversations over the past couple months. Although Edwin’s a new fireman, he’s well acquainted with the fires of life: raised by a tough-love single mom in Williamsburg, Brooklyn at a time when gangs, drugs, and violence were a daily reality, Edwin lit a fire in his heart to get out after seeing too many friends’ lives altered or cut short entirely.

It’s the kind of thing you share about yourself when you’re getting to know someone the way that Edwin and Pat were getting to know each other; kindling that gets a romantic fire going. And Pat might have added that her dad used to be a fireman of sorts, too, responsible for managing the fire that warms a construction site during overnight shifts. She might have also shared about the time her little brother, Charlie, set the kitchen on fire, a thank-god-it-could’ve-been-worse example of how she, like Edwin, had to grow up fast; in her case, as the eldest child of hardworking immigrant parents from Italy.

The phone rings. It’s Pat, and she’s calling to cancel because her bathroom’s out of commission. “I‘ll come fix it on Saturday,” Edwin says, “so we can keep our date on Sunday.” With his long hair and scruffy beard, Edwin shows up in character to fix the plumbing issue. The date is back on. The next day, Edwin knocks on the door. “Who are you?” asks Pat’s roommate. “I’m Ed. I was here yesterday, fixing the plumbing issue. I have a date with Pat.” He was unrecognizable, a plumber transformed into a prince; a long-awaited first date upgraded to a romcom meet cute that today is a family with three amazing kids.

If every stage in Edwin’s life can be described by fire - be it the fire of tough circumstances in his youth, the fire of responsibility in early adulthood, or the fire of romance in dating Pat - then for this present moment, the fire in Edwin’s life is Pat herself.

As our conversation continued, Edwin kept returning to Pat. She was the answer to every question, the point of every story. I said to Edwin, “You’ve come a long way in life from your childhood in Williamsburg to where you are now. What are the best decisions you’ve made? When did you start to find some stability in life?” He answered, “When I married Pat. She does everything, for our kids, for her parents, for my mom. I wouldn’t be where I am without her. Our kids wouldn’t be where they are without her. She’s the glue that holds us all together.”

If every stage in Edwin’s life can be described by fire - be it the fire of tough circumstances in his youth, the fire of responsibility in early adulthood, or the fire of romance in dating Pat - then for this present moment, the fire in Edwin’s life is Pat herself; so to continue Edwin’s story, I arranged a call with Pat, and she started by setting some expectations:

“I don’t beat around the bush, and I just come straight out and say things. You might have to filter me because I have no filter. I just come right out and say it. I’m not here to protect your feelings, or if I offend you, it is what it is. I’m not sugarcoating anything. I don’t talk like that, and I’m not going to be fake today.”

Pat was letting me know that she was going to be direct and brutally honest. You cannot come into contact with fire and expect anything less than its full light and heat. It has no dimmer switch, no thermostat, and neither does Pat.

I smile because I’ve seen this fire before, when I interviewed Pat’s brother, Charlie, and so I know this is a good and loving fire. I warm things up with my first question. “Edwin says you’re an amazing cook. Talk to me about that.”

“I was born in Sicily,” Pat begins. Sicilian food, she explains, is “peasant food,” today’s fresh dish formed from yesterday’s leftovers so that nothing goes to waste. Pat started cooking when she was just 8 years old, responsible for preparing the dinner that her mother started in the morning, a wooden spoon passed like a baton from one generation to the next. Just 8 years old but already entrusted with the family fire, in addition to serving as the family translator, the linguistic and cultural bridge between 1969 Sicily and modern day America.

“I have two boys and a girl. I want them to be tough cookies,” Pat says, “I want them to fight their own battles because I’ve had to fight mine and my parents’ my whole life.”

Unfortunately, Pat’s beyond-her-years burdens did not elevate her above childhood challenges on the receiving end of derogatory names that are uncomfortable for me to quote. Pat took these insults and used them as fuel for her fire, a lesson she impresses on her kids.

“I have two boys and a girl. I want them to be tough cookies,” Pat says, “I want them to fight their own battles because I’ve had to fight mine and my parents’ my whole life.”

She explains what it looks like to fight. “When you do something, do it with pride. I don’t care if it’s making a cup of coffee. Go above and beyond to show them that I did that and I’m proud of it. Don’t tell me about feelings hurt because I’ve had my feelings hurt nine million times over. It’s got to make you tough and it’s got to make you show the other person I’m better than you. You can call me every name in the book. I don’t care. Not only are you wrong, you’re going to be sorry for those words.” This is where the fires of Pat’s past, present, and future converge into a full blaze, a perpetual combustion of adversity into strength.

But you can’t have fire without a lot of heat. When her middle child was bullied by classmates for his red hair, Pat gave him wisdom to ward off the teasers while also reaffirming his own worth: “You tell them, ‘this is how God made me.’”

When the same child was later bullied by a teacher, she took a different tack, intervening directly to make sure that would never happen again. Pat explained, “You want your kids to learn to fight for themselves, but while they’re still young, you also have to be ready to fight for them.”

Like any parent of young kids, I worry about what’s happening when they’re away from me. Are they loved, lonely, or bullied? Are they able to defend and advocate for themselves? In Pat, I had someone in front of me who spoke with such strength and clarity about how to parent through these challenges, so I shared with her my concerns for my son, who is a very sweet and sensitive kid. “Gotta make him tough,” she said, “You want him to have empathy but you don’t want him to be picked on because he’s a softie.” It was what I expected to hear, but it was still hard to hear it.

“You, Pat, are a fire. I want to know if I have what it takes to be a fire for my kids and my family, just as you are for yours. Tell me, Pat, what does it look like to be a fire?”

I asked her another question, “What did you do when you heard about your son being bullied?” This question was not about my son nor was it about Pat. It was really about me and my doubts and insecurities as a parent. It was me saying, “You, Pat, are a fire. I want to know if I have what it takes to be a fire for my kids and my family, just as you are for yours. Tell me, Pat, what does it look like to be a fire?”

I was bracing for another admonition, but instead, Pat gave me a visual: “I went to the bathroom and cried,” she said. “I went to the bathroom and cried.” In other words, when a fire looks at itself in the bathroom mirror, a crying parent looks back. That’s exactly what I see when my kids are hurting, too.